Is

there value added that this book was written by someone who treats the disease and also has it himself? Does the following

sound familiar?

You’ve just experienced the anxiety, humiliation and pain of having your prostate

biopsied. Since the biopsy you have endured the sight of blood in your urine and bowel movements, blood in your semen, and

burning when you void. You have been told that the bleeding is to be expected, but to notify the doctor if you have fever

or difficulty voiding. If you have been sexually active, the blood that you and your wife saw was much more than you expected

when the doctor warned you of this possibility. You wonder if you have hurt something or if somehow the blood in your semen

could transfer anything to your wife. You wished you had asked that question. Now you begin to ponder the possible outcome

of the biopsy and whether it will be positive, and you feel a wave of intense anxiety churn across your chest. Although your

wife loves you and wants to help, you suffer this “waiting time” silently

and alone. Thoughts of the negative possibilities and how each could impact the people you love, your work, and your

longevity run rampant in your mind throughout the day and week. In an odd way you feel as though you have let your family

down just by being in this situation and the possibility of having cancer. Your anxiety increases as the day approaches for

the follow-up office visit to learn of the biopsy results; the butterflies return and become more frequent and intense. You

begin to think, “The doctor would have called by now if the results were good,” and this suspicion adds to the

tension. Your normal daily activities, work, going to church, playing tennis, whatever, feel surreal with the result of the

biopsy and its attendant ramifications looming over you. The days pass with the incessant mental examination of all the potential

possibilities. Thoughts like “what will I do if it’s positive” abound, but life goes on. You pay bills,

deal with your children, and handle other problems as if nothing else was going on with your health. That is all you can do.

You now glaringly understand the truism that life does indeed go on, and finally you transition into an attitude of acceptance:

“what will be, will be.” This newfound attitude of relinquishing control over life and the results of your biopsy

is, in a sense, a resignation, but it is comforting. Your preacher’s admonitions to “Give it over to God”

ring clear to you now and have relevance to you as never before. On the day of the doctor’s appointment to receive the

results, you leave work early, and the butterflies reappear yet again. They multiply in waves in the waiting room, reaching

an uninterrupted crescendo as your name is called and you are escorted to your chair in the exam room. There you wait, your

heart pounding so loudly that you feel those outside the room must hear it. Your thoughts turn again to the what-ifs: your

children, your wife, or someone you know who died of prostate cancer. You wonder if your affairs are in order and how your

parents would feel about having a son with cancer. The doorknob turns, startling you and the door opens. You attempt in vain

to read the expression on the doctor’s face, looking for signs of good news, but you realize that the doctor’s

face portends the news you hoped you would not hear. “I am sorry; I have bad news for you. Your prostate biopsy shows

cancer.”

I had

been checking my PSA for years and had watched it slowly creep up to just above normal. I decided to obtain a Free and Total

PSA to see if it would offer any guidance regarding pursuing a biopsy. (In your blood, a portion of PSA is free (unbound),

and a portion is bound by blood components. A low Free PSA indicates a higher possibility of a positive biopsy.) The day after

my blood was drawn, my nurse Tina approached me with the lab report indicating a very low Free PSA. She had drawn a frowny

face next to the lab value. I was crestfallen." Tina, did you really have to put the little unsmiley face on it?"

I decided at that moment that time had come for me to have a prostate biopsy. I asked one of my partners to do it at

lunch that very day, and the pathologist had the tissue samples in his hands by 1:30 p.m. The waiting began and my new life

as a patient commenced.

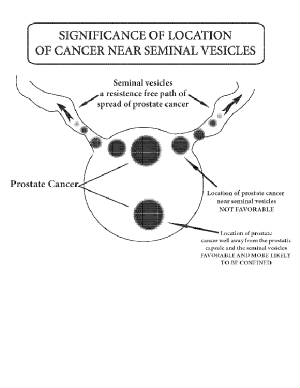

The luck factor: Whether you elect to have radiation or surgery, how well you do

depends a lot on just plain luck. If you choose

surgery, you are lucky if: Upon reviewing the final pathology report, all the cancer was confined to the prostate with

no seminal vesicle involvement, the Gleason score is predominately 6, and the volume of your disease is low. If the

volume of your disease is small, but the location involves the seminal vesicles, then your likelyhood of local spread increases

and your chance of cure decreases. It is purely a luck thing; as they say in business: location, location, location. If you choose radiation,

you are lucky if: Your body responds minimally to the deleterious effects

of the radiation from both the voiding and erectile function aspect, your PSA goes to .5 or lower and stays there, and there

are no long term radiation issues down the road. I had seen my surgeon only twice, once before the surgery and then during my hospital stay after

surgery. During the first meeting and after introductions, he asked me if I wanted to know any of the particulars of how he

performed a robotic prostatectomy. I said, "No." He then asked, "Do you want me to do the lymph nodes?"

I said, "No. I just want to be lucky and for you to have a good day." I added, " I do need directions to the

hospital from interstate I-85."

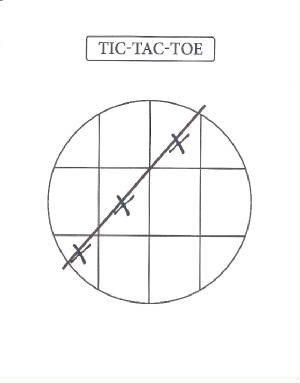

On the back of a paper bag at the kitchen table, I drew a picture of my biopsy report to show my wife

that only a small amount of cancer had been found and that I should do well with a good chance of cure. I remember being a

little emotional talking about it and trying to be up-beat so as not to alarm her. I worried that if she saw my distress,

it would cause her to be distressed too. After all, I am the breadwinner, father of our children, and her companion for almost

30 years. As I worried about upsetting her with all this information, she picked up the pencil and began to peer at the diagram

I had made. She put another positive area on the picture I had just drawn, then a line through the three areas, and said,

“Tic tac toe, John.” We stared at her handiwork almost mesmerized, and then she looked up at me and smiled. I

thought at the time that I had done a good job of allaying her fears, but in retrospect, maybe she sensed something in me

that prompted her to allay mine. Wives are smart that way.

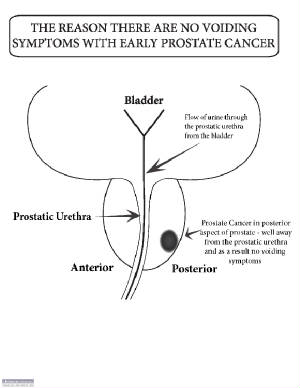

A

patient and friend who was 49 asked me at a party when he should have his prostate checked. I said that the blood work and

exam could be done in less than five minutes. I told him he could come by anytime at the end of his work-day through my office’s

back door, and I’d do the exam for free. He said that he was having no symptoms. I said that having no symptoms

is irrelevant. He then told me he had had a colonoscopy and asked if that checked the prostate. I said no, that was a

different organ. He said, like most people, “Isn’t prostate cancer a disease of old men?” I said, “No,”

and mentioned that Frank Zappa died in his 50s, three years after the diagnosis of prostate cancer, adding, “It’s

a painful death.” I made the point that it would be prudent for him, even at age 49, to be checked. My friend then said,

“but Frank Zappa had a bad lifestyle.” I replied that lifestyle was irrelevant as a risk factor for prostate cancer.

In the matter of a two-minute conversation with this college-educated friend, he had verbalized almost all the half-truths

regarding prostate cancer. He confirmed to me yet again why prostate cancer is sometimes diagnosed late, and revealed to me

another damaging half-truth I’d never heard before: the “But I don’t have a bad lifestyle” objection

to having a rectal exam. Frank Zappa-Link

|

John C. McHugh M.D. 660 A Lanier Park Dr. Gainesville, Georgia 30501

|

|

|

|